The Great Race got started in 1983, when three car nuts decided to stage an antique car rally from Knotts Berry Farm near Los Angeles all the way to the Indianapolis 500 Speedway in Indiana. Partly inspired by the 1965 movie comedy “The Great Race” with Tony Curtis, Jack Lemon and Natalie Wood, the rally was limited to pre-World War II cars and boasted a winner’s prize of $250,000. The 62 finishers were escorted through Race Week traffic by the National Champion Motorcycle Drill Team and onto the Speedway track for a well-deserved victory lap.

In the years since then, the event has evolved into an annual nine-day time-speed-distance (TSD) rally, with a $50,000 first prize and a total purse of $150,000, and cars allowed up through 1974. In most years 100 to 120 cars compete. The route varies wildly from year to year; in 2024 going from Owensboro, KY to Gardiner, ME and in 2025 from St. Paul, MN to Lake Murray, SC. (See GreatRace.com.)

A TSD rally is not a race, and speed limits are not broken. Rather, navigators are given a very detailed set of instructions 20 minutes before each day’s start, and must follow the instructions exactly. Typical instructions might be “turn right at the stop sign, go exactly 25 mph for 40 seconds, then increase to 45 mph and turn right at the first paved road.” If navigators (who have a much tougher job than the drivers) make a mistake, then the team can literally end up in the wrong state, since no GPSs, maps, radios, smart phones, digital watches, computers or other navigational devices are allowed. Competitors may install very accurate clocks and speedometers and can carry an analog stopwatch. Cars start one a minute, so the rally is not a parade (which would need a permit), and this makes it more difficult for novices to “puppy dog” behind expert teams.

The goal is to exactly mimic to the second the “ghost car” represented by the instructions. Actual cars are always trying to catch up to the ghost car, since the ghost accelerates and decelerates instantaneously, while actual old cars always lose time in each maneuver. So each team must calculate this loss and try to compensate. A perfect score for the day wins an “Ace” sticker, and the overall winner is often only a minute or two off the perfect time, after ten days of rallying! Secret checkpoints along the way record the exact time the competitors pass, and then compare that time to the “perfect ghost car” time.

Cars compete in divisions, including Grand Championship, Expert, Sportsman, Rookie and X-Cup (the latter for high school or college teams), and a handicap is given for older cars. The entry fee is $6500 per car for private entries and $9000 for corporate entries.

Each day the competitors transit on highways and Interstates, then rally in TSD mode for several hours, two or three times per day. The rally usually focuses on small towns and back roads (and thus the Great Race does not get much national media coverage). At lunch the cars roll into a small town destination, where local car clubs and crowds have gathered to see the cars come in, stop for 45 minutes for lunch, then roll out, one a minute. At the end of the day all the cars have a free “park ferme” car show for an hour or two, where again car clubs, bands, and crowds view the cars and their crews. Often this is the biggest event of the year in each small town.

My wife and I competed in the Great Race in 2005 in our 1968 “Bullitt” 390 Mustang GT fastback, identical to the famous car from the Steve McQueen movie by that name. (The rather rusty and well-used movie car was auctioned off for $3.74 million in 2020 – our car is probably worth 2% of that, but ours IS in much better shape!) We were able to stay on course and actually won one “Ace” perfect leg award, more by luck than expertise.

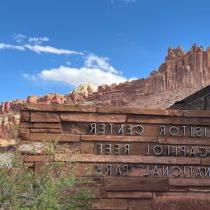

Back then in 2005 the Great Race ran 15 days, and our route was from the west front of the US Capitol in DC to Tacoma, WA, about 4500 miles. What we really enjoyed was the terrific scenery on the back roads, and getting treated like rock stars at each stop. We even got autograph requests from many kids, and police officers enroute wanted their pictures taken with one of the most famous movie cars in history. The only things we didn’t like were the July temperatures of 80 to 95F degrees, and no air conditioning in the (then) 37-year-old car. After that trip my wife-navigator made it clear: “It’s AC or no navigator!” AC was quickly installed.

The Great Race is one of the safest events in motor sports, with no fatalities in four decades of rallying. But there was one incident on the terrifying Mt. Washington in New Hampshire in 2018, when one of the Great Race cars, a 1955 Buick Estate, was headed down the mountain, braving the 1000-foot cliffs with no guard rails. Behind the Buick was a 1964 1/2 Mustang driven by Scott Henderson and navigated by his daughter Mallory, both from Mobile, Alabama.

What happened next can still be seen on the Henderson’s GoPro at: http://www.facebook.com/HendersonGreatRace2014/videos/2011356065794388/

Suddenly the Buick lost its brakes and started accelerating down the mountain toward a cliff. The driver, Carl Schneider, intentionally ran the Buick up a hillock of rocks, and the car turned onto its side. But it kept sliding down the gravel road, hit another rock, and flipped back onto its tires, and kept heading down toward certain death. Scott Henderson calmly and quickly raced past the Buick and turned left, blocking the Buick and stopping it. No-one was injured. The Mustang only suffered a small dent, which is still preserved as a badge of honor. Scott was the hero of the day — what a guy!

Next month I will describe the 2024 Great Race as it crossed into Maryland and Virginia, going through beautiful countryside we had never seen before.

Photos courtesy Lew Toulmin

- 1. A James Bond almost look-a-like Aston Martin on the Great Race (GR) in 2018. Experts will spot that this is not James’ type of AM DB-5 (worth about $1.2 million+), but rather the later and less valuable DB-6 (worth perhaps half that, depending on condition).

- 2. A 1936 Ford police car on the Great Race in 2018, driven by Jim and Louise Feeney. They competed for many years in the Great Race, and always drove their car to and from the start and finish, no matter how many thousands of miles away from their home in New York state. The car is numbered “54” as in the famous 1960s TV comedy show “Car 54 Where Are You?” But in the TV show, the actual car was a quite different 1962 Plymouth Savoy 4-door sedan.

- 3. A 1917 Peerless Green Dragon 330 cu. in. V-8 on Mt. Washington in the 2018 Great Race. The car has rallied for more than 150,000 miles, and the interior gets so hot that the crew must wear a special Coolshirt system which circulates ice water around their bodies.

- 4. An “Ace” sticker from the 2005 Great Race awarded for a perfect leg (matching the “ghost car” instructions to the second). We earned one such award in 2005 on the GR from the US Capitol in DC to Tacoma, WA. The gecko lizard driver shows that the major race sponsor that year was GEICO.

- 5. Our 1968 “Bullitt” Mustang 390 GT fastback, identical to the Steve McQueen movie car, with its 2005 Great Race sticker on the side. Our car is in the foreground at dawn on the Mall, and the original “Bullitt” Mustang movie car, worth over $3.7 million, is in a glass box in the distance. We have driven our “Bullitt” across the entire US three times.

- 6. A wild-looking 1957 Porsche Speedster driven by Carl and Mary Webster in the 2024 GR. Only 1171 were made in 1957, and prices range from $38,000 to $340,000 depending on condition and provenance. Some eligible GR cars can be purchased for as little as $25,000. Be aware that there is already a waiting list to enter the 2026 Great Race.

- 7. A screen grab of the incident on Mt. Washington, New Hampshire in the 2018 GR. The 1955 Buick Estate flipped back onto its tires and was headed for a cliff, when competitor Scott Henderson blocked the Buick with his Mustang and prevented a fatal accident.

- 8. Interior of a GR car, with a super-accurate Speedwise speedometer on the left, a large dial clock in the middle, and a rolling set of TSD rally instructions on the right. There are often several hundred instructions per day – miss just one and you not only lose the race, you might end up lost in the wrong state!

- 9. If you have to “phone a friend” while fixing your GR car, you know you are in deep monkey.